In-depth: Understanding the impacts of changing Arctic storms

Source: CarbonBrief

For ships sailing close to the north pole, few events pose bigger risks than an Arctic storm.

Arctic storms can unleash extremely high winds, which churn up the ocean, causing waves to swell by several metres. This not only makes life at sea unbearable for sailors, but also makes navigating the Arctic – and its icebergs – more challenging.

Strong winds can also tear through the sea ice, causing it to break apart and move off in different directions. A growing field of research suggests that the impact of stormy winds on sea ice could be larger than previously thought – and potentially significant for forecasts of future ice loss.

There is emerging evidence, too, to suggest that Arctic storms could be affecting weather away from the poles.

“The short answer is there is some impact on the mid-latitudes from Arctic cyclones, but we don’t know with what regularity that happens,” says Dr Ola Persson, a polar meteorologist from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Persson is one of 600 people taking part in MOSAiC, the largest Arctic research expedition ever attempted. (Carbon Brief recently joined the expedition for its first six weeks.)

Inside MOSAiC

- Inside MOSAiC: How a year-long Arctic expedition is helping climate science

- Interactive: When will the Arctic see its first ice-free summer

- Explainer: How ‘Atlantification’ is making the Arctic Ocean saltier and warmer

As part of the expedition, Persson and his colleagues have set up an array of instruments to measure different aspects of Arctic storms – from the speed of the winds they bring to the scale of their impact on the sea ice.

Gathering such data could help to answer key questions about Arctic storms, such as how they could be affecting long-term ice and climate conditions and how, if at all, they could be shifting in response to climate change.

Twisted

“Arctic storms” – also called Arctic or polar cyclones – are low-pressure systems that affect the Arctic Ocean and its nearby land masses, including Greenland, northern Canada and northern Eurasia. In an Arctic storm, the air spirals counterclockwise.

The animation below shows the movement of Arctic storms across the northern polar region in 2012 – a record-low year for sea ice. In the animation, the movement of surface winds is represented by small arrows coloured according to velocity.

The movement of summer storms across the Arctic in 2012. Credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio

Arctic storms can form both in and out of the polar region, says Persson. “Some of them seem to originate as cyclones coming from the lower latitudes and moving into the Arctic. Other Arctic cyclones do seem to develop in the Arctic region.”

Storms that originate in the Arctic can form when there is a disturbance in the “tropopause” – the part of the atmosphere that acts as a boundary layer between the troposphere and the stratosphere, says Persson. “These disturbances can be very long-lived and, if the conditions are right, they seem to induce a low-level cyclone.”

In comparison to tropical storms (known as typhoons or hurricanes depending on where they are found) there has been very little research into Arctic storms, Persson says.

This is largely because, in comparison to mid-latitude storms, Arctic cyclones affect very few people. However, rapid sea ice decline is making the Arctic easier to navigate for longer periods of the year. This in turn has sparked a boon in both commercial and tourist activity in the Arctic – making the need to understand Arctic storms more urgent.

There is also some evidence to suggest that climate change could be making Arctic storms more frequent, says Prof Jenny Hutchings, a MOSAiC scientist and researcher of sea ice dynamics from Oregon State University. “There seems to be an increase in cyclone activity up to the Arctic,” she tells Carbon Brief.

However, the lack of historical data on Arctic storms makes it difficult to establish whether there is an increasing trend, says Persson:

“There is some suggestion that Arctic cyclones may be more frequent now, but the problem is we don’t have a whole lot of measurements from before. Maybe the previous lower frequency we’ve observed is due to the fact that our models, or our reconstructions of the past, aren’t complete enough.”

Another aspect of Arctic storms that scientists are yet to get a clear picture of is their physical structure, Persson says:

“Arctic cyclones seem to have a different structure than mid-latitude cyclones. There’s been some studies in the last two to four years that have suggested that they have a vertical structure that is more similar to a hurricane than to a mid-latitude storm.”

During the MOSAiC expedition, he aims to gather data on the vertical structure of Arctic storms. The expedition is centred around the Polarstern, a German icebreaker that has been deliberately frozen into the sea ice. The vessel will drift passively with the ice as it moves northwards over the next year.

Map showing the Polarstern’s route from its departure from Tromso on 20 September 2019 to around 85 degrees north in the Central Arctic Ocean, where it attached itself to an ice floe on 6 October 2019 (red). The thatched arrow illustrates the area that the ship might drift over on its year-long journey, which will end near the Fram Strait. Credit: Tom Prater for Carbon Brief

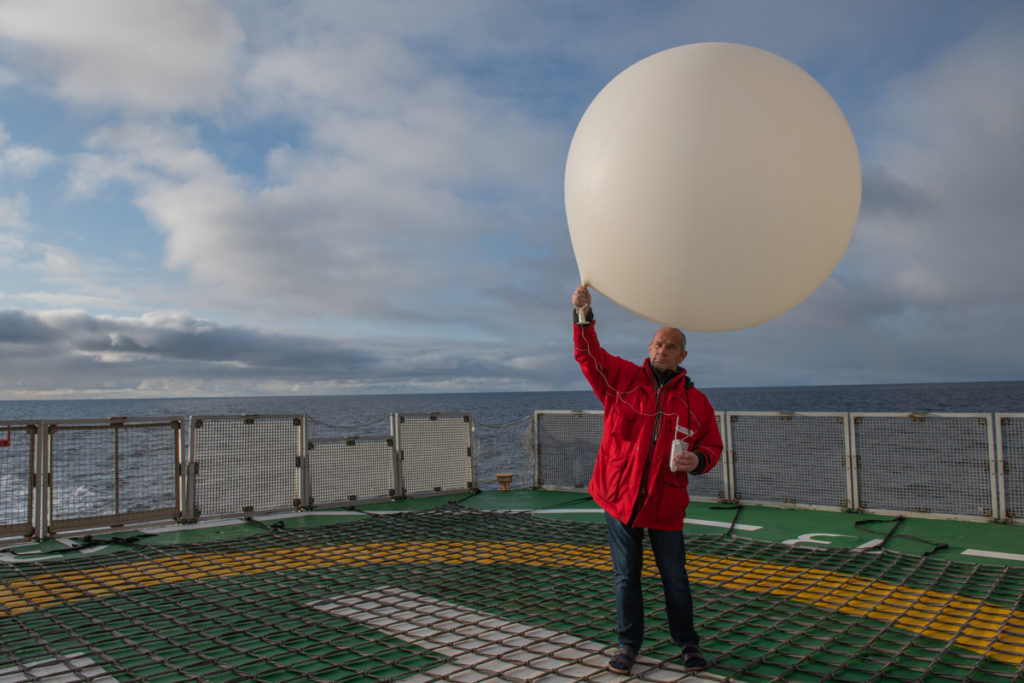

Map showing the Polarstern’s route from its departure from Tromso on 20 September 2019 to around 85 degrees north in the Central Arctic Ocean, where it attached itself to an ice floe on 6 October 2019 (red). The thatched arrow illustrates the area that the ship might drift over on its year-long journey, which will end near the Fram Strait. Credit: Tom Prater for Carbon BriefIn order to study the structure of Arctic storms, Persson and his colleagues will need to wait for them to pass over the ship. They will then collect data on the storms using a series of instruments, including weather balloons, which capture changes in atmospheric temperature, pressure, humidity and wind. They will also use specialised weather radars, which use radio waves to detect changes in precipitation and wind speed.

The array of instruments will take measurements at different heights in the atmosphere during a storm. By piecing together this information, the researchers hope to learn more about the vertical structure of passing Arctic storms.

Juergen Graeser launches a weather balloon on the helicopter deck of Polarstern. 22 September 2019. Credit: Esther Horvath

Break the ice

As well as investigating the structure of Arctic storms, MOSAiC researchers will also try to get a picture of how they can impact the sea ice. Persson says:

“What people have been noticing in the past few years is that when we have a really big Arctic cyclone, the sea ice disappears.”

A dramatic example of this occurred in 2012, when the Arctic was hit by a powerful, slow-moving storm in August. The cyclone lasted almost two weeks, bringing heavy rain and 30mph winds.

That year, Arctic sea ice reached its lowest level on record. It is possible that the storm played a role in driving the rapid downturn in sea ice.

Scientists have hypothesised that the storm enhanced ice loss by causing the ice to break apart, leaving it more vulnerable to melting. The stormy winds may have even pushed ice into warmer waters, further enhancing melting, say researchers.

However, other researchers have argued that the storm only played a minor role in the record low.

A study published in 2013 analysed the impact of the storm using climate modelling. The researchers ran two sets of simulations: one mirroring Arctic conditions in 2012 with the August storm included and one mirroring 2012 conditions without the storm.

The research found that, in both sets of simulations, Arctic sea ice fell to a new record low. However, in the simulations including the storm, the record low was set around 10 days earlier than in the simulations without the storm.

The findings suggest that other factors were more important for the record-low ice conditions seen in 2012, the researchers said. For instance, that year, Arctic summer temperatures were warmer than average and the ice pack consisted largely of “first-year ice” – young ice that is more prone to melting.

Changes in the extent of Arctic sea ice aged less than one year (light blue) to ice aged four years and over (dark blue) over time. Extent is shown for the same week (22-28 October) from 1985-2019. Data source: National Snow and Ice Data Center. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts

While the study helped shed light on the 2012 cyclone, the true impact of Arctic storms on sea ice remains largely unknown. “We only looked at one big storm,” said study co-author Dr Ron Lindsay, from the University of Washington in 2013. “If we want to understand how storms will affect the ice cover in the future we need to understand the effect of storms in different conditions.”

One of the research aims of the MOSAiC expedition is to study the impact of Arctic storms on the sea ice for an entire year, under a vast range of conditions.

In a 50km-radius around MOSAiC’s main ice camp, scientists have installed a network of floating research stations. These stations are home to a series of instruments that, for the next year, will take near-continuous measurements of changes in the atmosphere, sea ice and ocean.

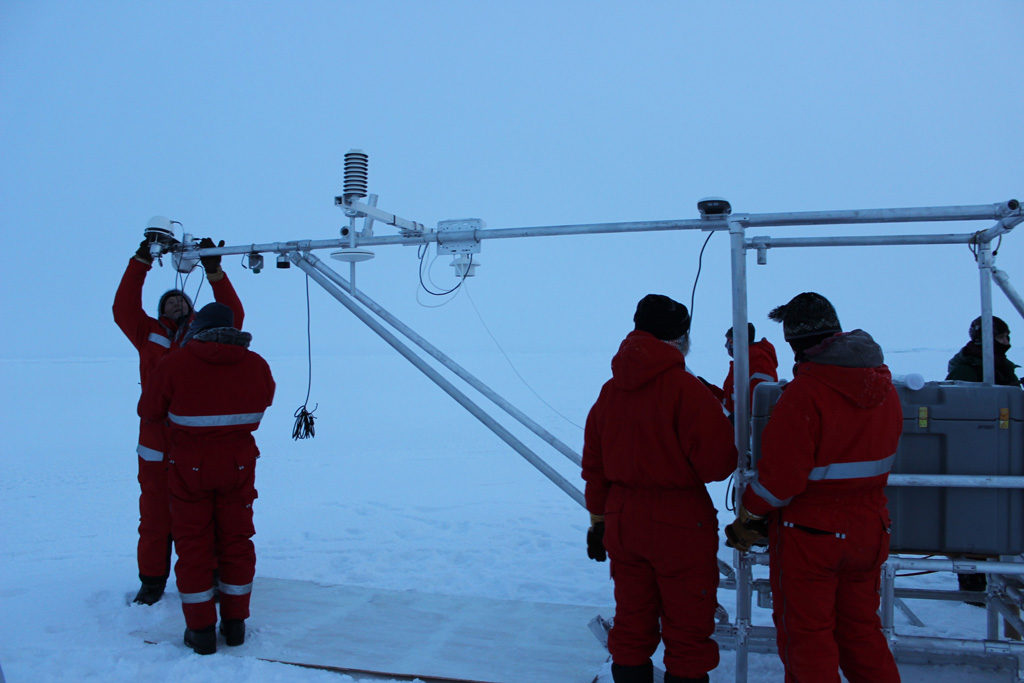

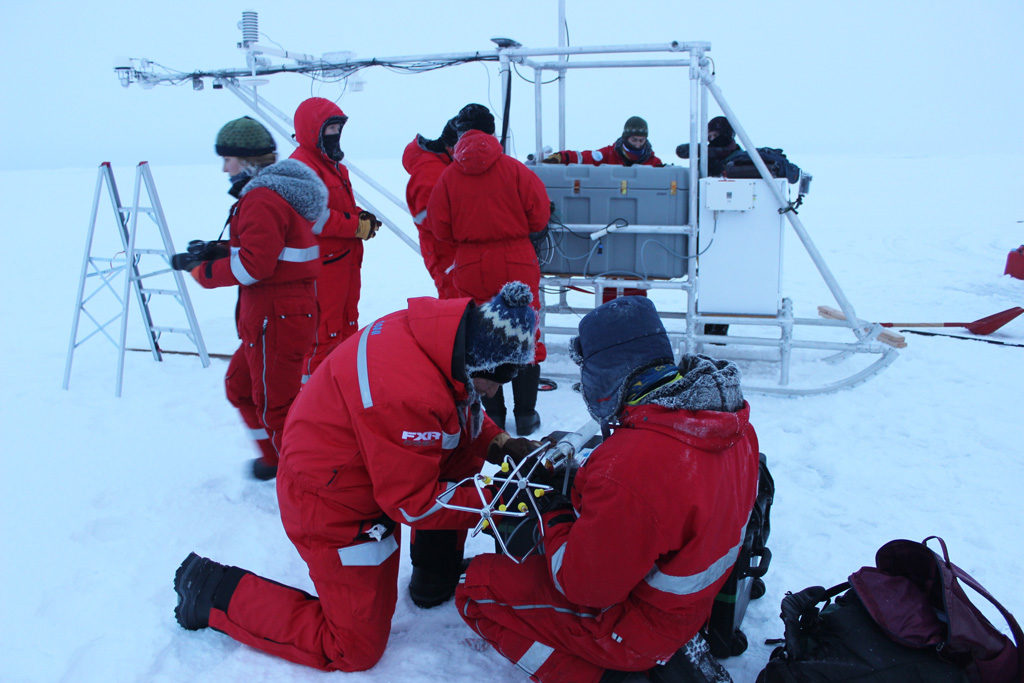

Dr Ola Persson and other MOSAiC scientists set up a scientific instrument in the Central Arctic Ocean. Credit: Daisy Dunne for Carbon Brief

One of these instruments, a giant metal sledge set-up by Persson and his colleagues, will be used to study Arctic storms. The sledge is covered by various pieces of equipment measuring changes in the atmosphere.

The most important bit of kit for monitoring passing Arctic storms is a “sonic anemometer” – an instrument sticking out from the side of the sledge that uses sound waves to measure changes to wind speed and direction.

Dr Ola Persson and a colleague attach a sonic anemometer to a scientific instrument in the Central Arctic Ocean. Credit: Daisy Dunne for Carbon Brief

The sledge also features an advanced GPS system, which allows researchers to track the location of the ice floes in real time.

Using these instruments, the researchers plan to monitor the speed and strength of winds during storms – and whether these winds cause the sea ice to break apart and move off in different directions.

“We’re going to hopefully be able to map out the response of the ice during a cyclone and see if the high winds brought by cyclones causes the ice to diverge,” says Hutchings.

The research is risky. A particularly severe storm could cause the sea ice to split in two or break apart entirely, causing the researchers’ instruments to fall into the ocean.

“That’s something that will be interesting to see, which ice floes survive in the end – and which don’t,” says Dr Thomas Krumpen, a sea ice researcher from AWI and co-cruise leader onboard the Akademik Fedorov.

The measurements taken until the expedition’s end in September 2020 could hopefully shed more light on the impact of Arctic storms on ice cover.

Storms on the run

One reason that MOSAiC scientists are keen to gather data on Arctic storms is that some evidence suggests that they could affect climate conditions away from the poles.

This is because, under certain conditions, it seems that Arctic weather can escape the polar region and reach down into the mid-latitudes, Persson says.

An example of this occurred in early 2019, when parts of the US and Canada were struck by an extreme cold snap that sent temperatures plummeting to -17C and below.

A man digs out a red Chevrolet car from the parking lot snow in the morning. Toronto, Canada. 29 January 2019. Credit: Torontonian / Alamy Stock Photo

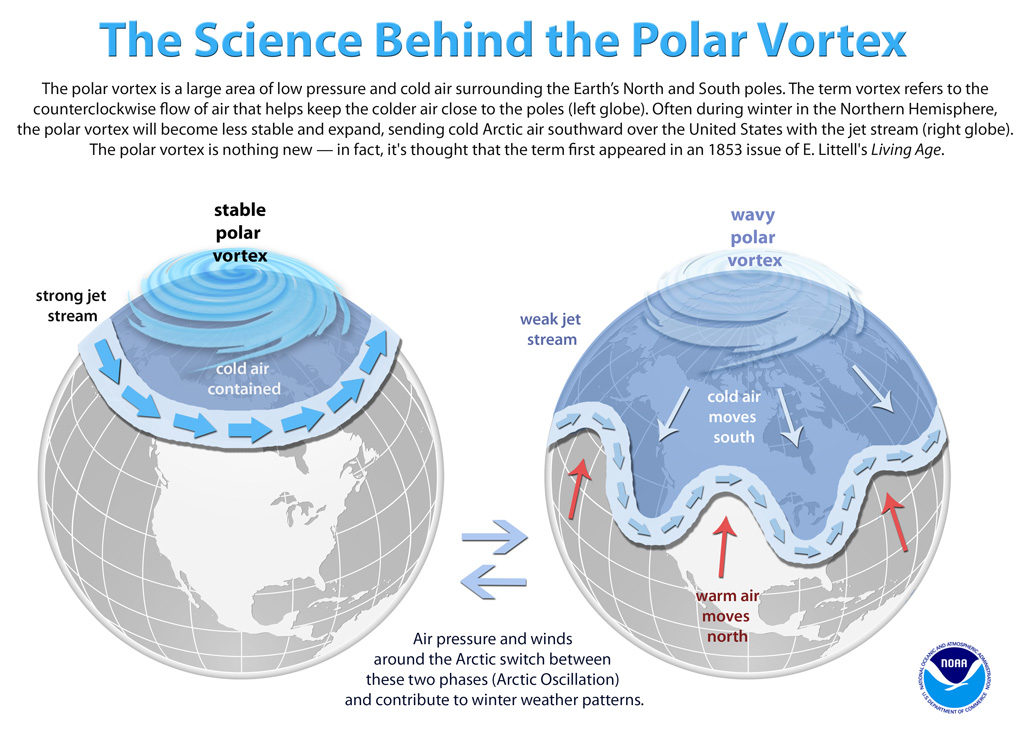

Though the science is not yet certain, it seems that Arctic storms can move out of the Arctic and into the mid-latitudes when there is a disturbance in the “stratospheric polar vortex” – a low-pressure weather system that sits around 50km above the Arctic.

When disturbed, the polar vortex can become weakened – allowing the cold weather that it usually contains to spill out into the mid-latitudes. “[This] brings a lot of cool air and spins up a lot of storms and snowfall,” says Persson.

The diagram below demonstrates how a weakened polar vortex can allow cold Arctic weather to escape from the northern pole.

The science behind the polar vortex. Credit: NOAA

Though the mid-latitudes have seen several notable cold snaps in recent years, it is not yet clear whether such events are becoming more likely, Persson says.

By collecting data on the movements of Arctic storms over the course of MOSAiC, he hopes to gain a better understanding of how often they travel out of the Arctic. “The short answer is there is some impact on the mid-latitudes from Arctic cyclones, but we don’t know with what regularity that happens.”